Share

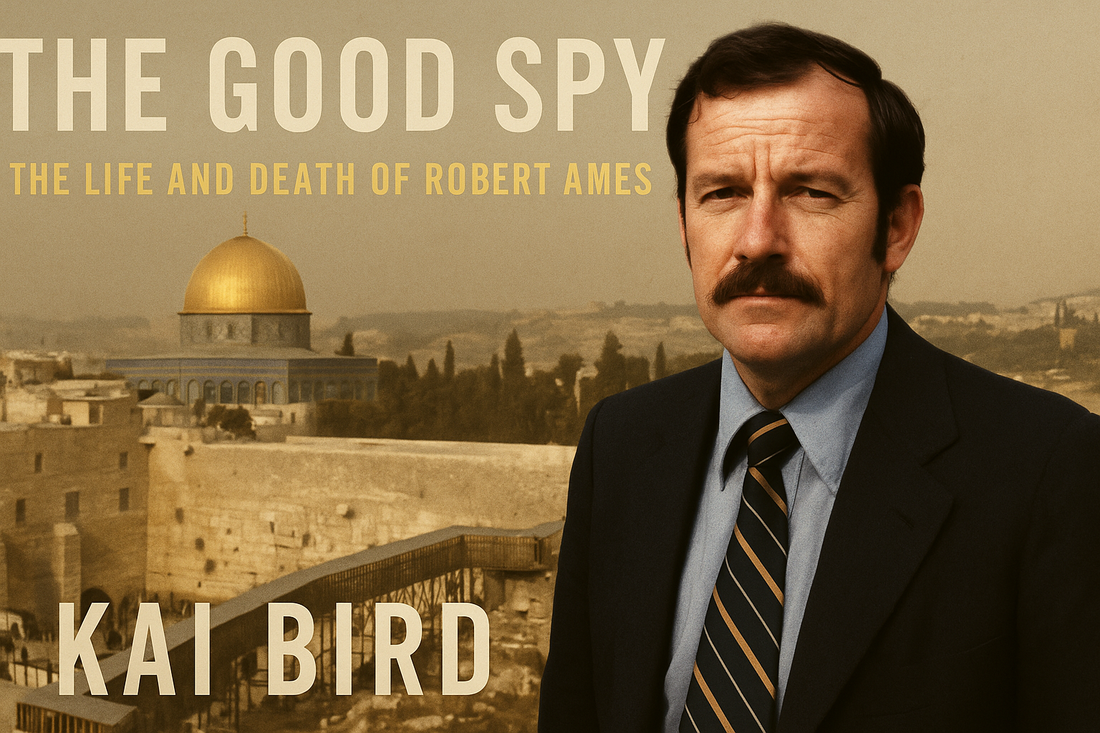

The Good Spy by Kai Bird: How One CIA Operative Tried to Broker Middle East Peace

Uncovering the Life and Legacy of Robert Ames—The Unsung Diplomat Who Opened Backchannels Between the U.S. and the PLO

Suppose James Bond had a soul, a mortgage, and a fluency in Arabic. In that case, he might have resembled Robert Ames—a man who didn't swagger out of explosions but quietly stepped into rooms and made the impossible happen by drinking too much sweet tea and listening more than he talked. In The Good Spy, Kai Bird does the near-unthinkable: he turns a CIA officer's life into a heartbreakingly human tale about diplomacy, decency, and the bloody ballet of Middle Eastern politics.

Bird, no stranger to dense subjects and dense environments (see: American Prometheus and presumably every cocktail party he's ever been to), takes on the shadowy biography of Ames—basketball star turned Arabist spook turned footnote in a conflict that has eaten up footnotes for breakfast. But here, he plucks Ames from the anonymous crowd of Cold War cloak-and-dagger men and gives him the elegy of an unheralded statesman. If Miles Copeland and Kermit Roosevelt were the CIA's rockstars—tousled hair, reckless policies, questionable rhythm—then Ames was the guy in the back writing actual music.

It begins, fittingly, with a ghost—a 1993 photo-op on the White House lawn, where Clinton finagles a handshake between Rabin and Arafat. But Bird quickly rewinds, arguing that this moment of performative diplomacy would've been impossible without the groundwork laid by Ames—dead a decade prior, buried under the rubble of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut. His absence, a tragic loss, is deeply felt in the narrative.

Ames, we learn, was not your average covert cowboy. He hated violence—preferred conversation. Thought satellites were all very lovely, but that real intelligence came from people—messy, paranoid, contradictory people. And it turns out he was very good at talking to them. Over two decades, he builds quiet friendships with men the U.S. public would be taught to fear: most notably, Ali Hassan Salameh, the PLO's security chief and one-time public enemy number one in Israel. (Known to some as "The Red Prince," to others as "the guy the Mossad wanted dead.”) Their backchannel correspondence, largely invisible to the broader U.S. government, allowed for a rare and improbable glimmer of diplomacy between the PLO and the West. Think of it as When Harry Met Sally, but if Sally were a Palestinian intelligence officer and Harry knew seven ways to escape a tail in Beirut traffic. Ames' human side, his empathy and his desire for peace, make him a relatable and endearing character.

Bird is at his best when things get murky. He doesn't shy away from the contradictions: Ames admired Salameh, grieved his death, and still knew full well what his friend had done. He also doesn't flinch from Ames' blind spots. The CIA man may have been fluent in Arabic and empathy, but Bird subtly suggests that his loyalty to his sources could sometimes blur into a kind of selective idealism. Ames, it seems, wanted peace so badly he could taste it—and sometimes, perhaps, mistook that desire for actual progress.

That said, The Good Spy is no hagiography. It's a layered, gripping study of a man who operated with more integrity than most, inside a system that frequently punished integrity as a character flaw. Bird manages to explain the knotted, century-spanning blood feud of the Levant without sending the reader sprinting for a glossary, and he does it all while keeping Ames at the centre of the stage. The book's depth and complexity will keep you intellectually stimulated. There are no cardboard villains here—just men trying to shape the world through whispers, while dodging bullets and bureaucrats alike.

The final chapters—dealing with the embassy bombing, the murky role of Iranian-backed militias, and the faint, fading echo of what Ames might have achieved—are haunting. Especially Bird's revelation that the perpetrator may have ended up in CIA protective custody. There's gallows humour in there somewhere, but mostly it just makes you want to scream into a filing cabinet.

In the end, The Good Spy is less a spy thriller than a long, wistful sigh. It's a biography, yes, but also a requiem—for Ames, for Salameh, for the fragile promise of diplomacy conducted by men who cared. Bird doesn't tell us what would've happened if Ames had lived, but he doesn't need to. The ghosts on that White House lawn are answer enough.

Rating: Five encrypted briefcases out of five.

(A rating system so secret even the author doesn't know what it means.)