Share

The Art of Rivalry: How Competition, Chaos, and Friendship Shaped Modern Art’s Greatest Masters

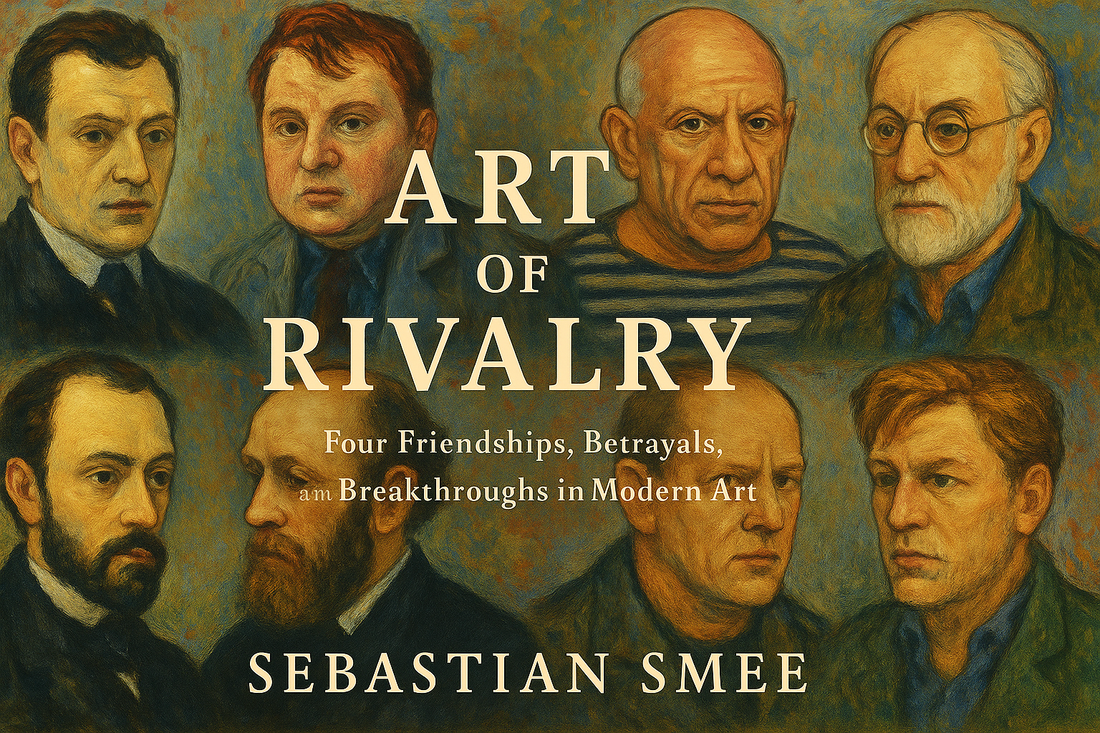

Explore the explosive relationships between Freud & Bacon, Manet & Degas, Picasso & Matisse, and Pollock & de Kooning in Sebastian Smee’s gripping study of genius born through rivalry.

If you've ever imagined the great modern artists as lone wolves toiling away in monastic silence, Sebastian Smee’s The Art of Rivalry will shatter that illusion. What Smee presents is the art world’s version of Fleetwood Mac: brilliance forged in break-ups, breakdowns, booze, and bouts of unbearable egotism. He has taken four artist duos—Freud and Bacon, Manet and Degas, Picasso and Matisse, and Pollock and de Kooning—and peeled back the canvas to reveal the chaos beneath. It's a paradigm shift, to say the least.

This is a book where bruised egos drive brushstrokes, and where admiration festers into envy faster than you can say “impasto.” Smee, a Pulitzer-winning art critic who knows his pigments from his Pontormos, threads a needle through the lives of eight men who were too talented, too damaged, and frankly too drunk to go it alone. And thank God for that. Because what emerges isn’t just a study in artistic excellence, but a juicy, occasionally deranged psychological thriller where the murder weapon is always the same: oil on canvas.

Let’s start with the Bacon and Freud chapter, because, honestly, who wouldn’t? Picture it: Lucian Freud, the neurotic grandson of Sigmund, peering out from behind a canvas like a startled dormouse. Enter Francis Bacon, a man who could outdrink a rugby team and still produce a masterpiece before breakfast. Their relationship is the emotional centre of the book—Freud’s obsession with Bacon is almost erotic in its intensity. Bacon, ever the charming sadist, reciprocated with brutal honesty and whiskey-soaked affection. It’s a tale of admiration teetering on the edge of masochism, and it had me Googling their paintings like a man possessed.

But while Freud and Bacon were passion and punishment, Manet and Degas were precision and prickliness: less heat, more hiss. Degas revered Manet—until Manet slashed a portrait Degas had painted of him. Talk about brushstroke betrayal. Their chapter is perhaps the most Parisian in temperament: all cigarettes, side-eyes, and subtle sabotage.

Then there’s Matisse and Picasso, the Cain and Abel of Cubism. What makes this pairing so joyous is that it spans decades of mutual admiration disguised as aesthetic warfare. Matisse was unaware for years that he was locked in a rivalry with Picasso—until Picasso sprinted past him, looked back, and grinned. Smee captures this dynamic beautifully, like a cultural commentator narrating a chess match between frenemies. And we get the added treat of Gertrude and Leo Stein playing the part of art-world gatekeepers, swapping allegiances like tennis fans at a five-set final.

Finally, there’s the Pollock and de Kooning chapter, which reads like an American gothic rock opera—this one brims with New York grit and a tangle of tragedies. Pollock, the volatile alchemist of the drip, wrestled with alcohol and acclaim like they were demons on his shoulder. De Kooning, no saint himself, was alternately his competitor and confidant. What began as camaraderie became collision. You can almost smell the turpentine and taste the cigarettes. This chapter spans the most enormous supporting cast—critics, patrons, muses, and casualties—with Peggy Guggenheim floating through like some war-era fairy godmother in furs and pearls.

And yes, the book includes a few colour plates—eight pages to be exact. But like me, you’ll soon be on a first-name basis with your printer, because the real gems, the works that Smee references in hypnotic detail, are nowhere in the book. You’ll need Google Images on standby and perhaps a corkboard to keep track of the emotional chaos.

What I appreciated most, apart from the delicious gossip and wincing emotional blows, is Smee’s rejection of the solitary genius myth. Art, he argues—persuasively and with wit—is not birthed in a vacuum. These masterpieces were not immaculate conceptions. They were the result of tension, envy, admiration, and, quite often, a bit of shouting in the studio. The Wright Brothers, Steve Jobs, and Jackson Pollock all had their co-pilots. We are not made alone, and neither is our art. Smee's book humanizes these artists, making their struggles and triumphs relatable.

A minor gripe: Smee, for all his candour, does give Picasso a baffling free pass on some genuinely revolting behaviour. The man leered at Matisse’s daughter, adopted a teenager, then painted her nude, and tormented nearly every woman he touched. There’s an attempt at psychological rationalisation—missing a dead sister, the elusive muse—but even with a palette as broad as Smee’s, you can’t whitewash that canvas.

Still, The Art of Rivalry is as compelling as any thriller and more instructive than a semester at the Courtauld. It made me want to revisit every gallery with new eyes and a heightened sense of tension. It reminded me that behind every masterpiece is a messy, meandering, sometimes toxic relationship that gave it life.

Read it if you want to understand the art. But reread it if you're going to understand the artists.

Rating: 5 carafes of absinthe out of 5

Best read with: A glass of red and a magnifying glass for your soul.