Share

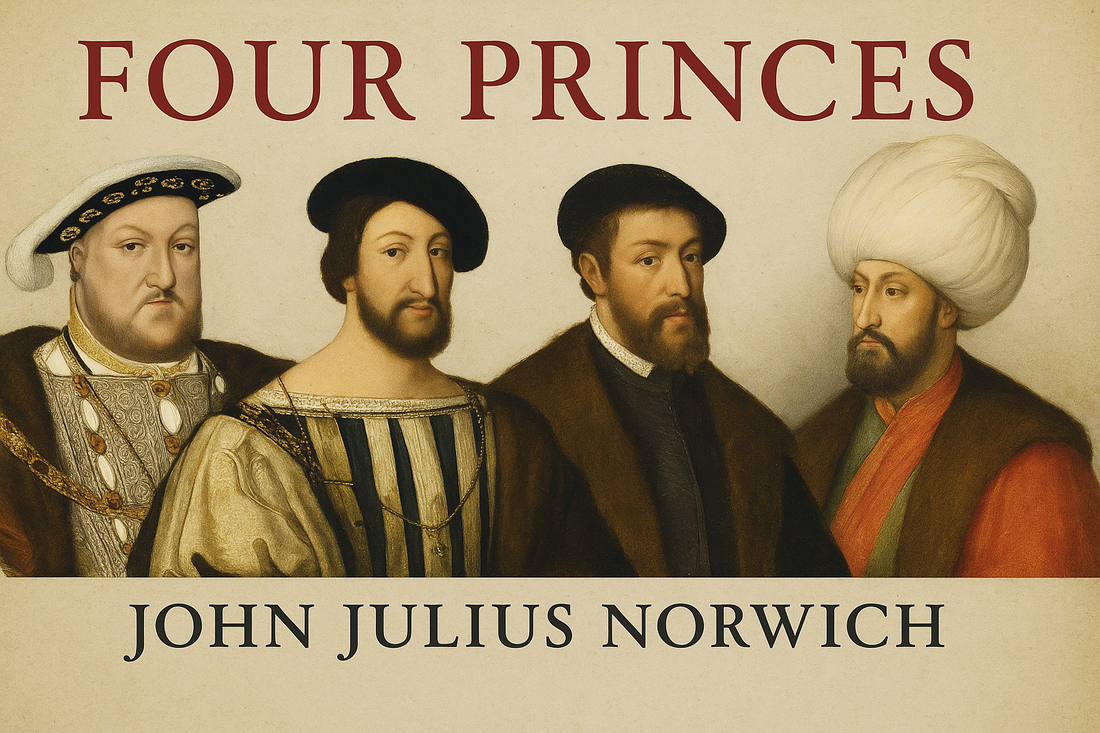

Four Princes by John Julius Norwich: Power, Politics, and the Shaping of Modern Europe

A witty yet critical review of Norwich’s royal quartet—Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, and Suleiman the Magnificent—and why it’s time to rethink the Ottoman Empire’s place in European history.

John Julius Norwich, with his impeccable tailoring and BBC diction, was a master storyteller. The son of Duff Cooper, a diplomat with a taste for imperial grandeur, and Lady Diana Cooper, society’s answer to a Greek statue, Norwich was born to translate the past into something charmingly palatable for dinner parties. His career, which spanned Oxford lectures, televised history specials, and books written in a distinct tone of patrician authority softened by wry affection, was a testament to his mission to ensure that history—particularly European history—never felt like homework.

Four Princes is perhaps his most accessible work: a brisk gallop through the early 1500s, starring four impossibly charismatic men who, by virtue of birth, ambition, and enormous hats, found themselves shaping the fate of Europe. You know the types: Henry VIII of England, who devoured wives and monasteries with equal appetite; Francis I of France, who preferred his warfare painted in oils; Charles V, whose Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, Roman, nor particularly manageable; and finally, Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Sultan who somehow kept his cool while the Christian boys threw tantrums across the continent.

Norwich organises his tale like an elegant dinner conversation—never too heavy, never too long, and constantly looping back to a good anecdote. And there’s absolute pleasure in watching these four egos clash, flirt, and sometimes collaborate on the grand chessboard of Europe. This isn’t a deep dive into archival scholarship—this is history as opera, with velvet capes and battle standards waving in the breeze.

But here’s where the candelabra wobbles a bit.

For all his wit and storytelling flair, Norwich can’t quite bring himself to treat Suleiman as an equal protagonist in this Renaissance drama. The Ottoman sultan is the only one whose brilliance is tinged with exoticism. Where Henry and Francis are human—flawed, yes, but relatable in their pettiness—Suleiman is described with a sort of silk-draped reverence that smells faintly of spice markets and Edward Said’s ghost whispering, “Here we go again.”

It’s the same old song: East as other, as outside, as somehow mystical rather than modern. But the truth—less romantic, more political—is that Suleiman wasn’t hovering on the periphery of European affairs. He was in European affairs. His empire stretched across the Balkans and deep into Hungary. His navy ruled the Mediterranean. His alliances—most notably with Francis I of France—literally redrew the map. If there’s one thing Norwich’s otherwise brilliant book fails to do, it’s to bury the tired old notion that the Ottomans were somehow not part of Europe.

The alliance between Francis and Suleiman is perhaps the most delicious—and consequential—subplot in the book. Here, you had the King of France, a Catholic and stylish monarch, locked in endless rivalry with Charles V, who ruled over everything from Spain to the Habsburg lands to the Netherlands. And then, like a scene from an early modern buddy comedy, Francis goes and teams up with Suleiman the Magnificent, the Muslim sultan, to outflank his Christian rival. It's a geopolitical masterstroke that is both intriguing and fascinating.

It scandalised everyone. It infuriated Charles. But it worked. The Franco-Ottoman alliance, often quietly dismissed in Western tellings, was a geopolitical masterstroke. It stabilised France’s eastern borders. It distracted Charles V with campaigns against the Turks in Hungary and the Mediterranean. And it proved, once and for all, that the boundaries between “Europe” and “the East” were far more porous than Norwich’s prose sometimes allows.

Suleiman wasn’t a footnote or a sideline threat; he was a full-blown participant in the power plays of Christendom. He played it better than most. While Henry was busy changing wives and founding new churches out of spite, and Francis was commissioning tapestries of his magnificence, Suleiman was reforming tax law, reorganising his court, and penning poetry that put the Tudors to shame.

To Norwich’s credit, he admires Suleiman. But admiration, in this case, doesn’t equate to integration. The Ottoman Sultan still feels like the exotic other in a book that otherwise reads like a Renaissance bromance. It’s a missed opportunity in a work that otherwise does so much right: tracing the tangled web of ambition, ideology, personal vanity, and political pragmatism that defined 16th-century Europe. It's a call to look beyond orientalist stereotypes and see the full picture.

Still, Four Princes remains a thoroughly enjoyable read. Norwich’s charm is infectious. His pacing is impeccable. And his anecdotes—whether it’s Henry’s jousting accidents or Francis’s obsessive rivalry with Charles—are told with just the right amount of theatricality. It’s a history book that doesn’t pretend to be more than what it is: a grand, sweeping portrait of four men who shaped their world and, by extension, ours.

But when you reach the chapters on Suleiman, read a little deeper. Ignore the incense and the golden turbans. Look past the orientalist brushstrokes. Because what you’ll find—if you do—is a ruler every bit as central to Europe’s story as the kings who sat in Versailles or Westminster. And perhaps more deserving of the title Magnificent than any of them.