Share

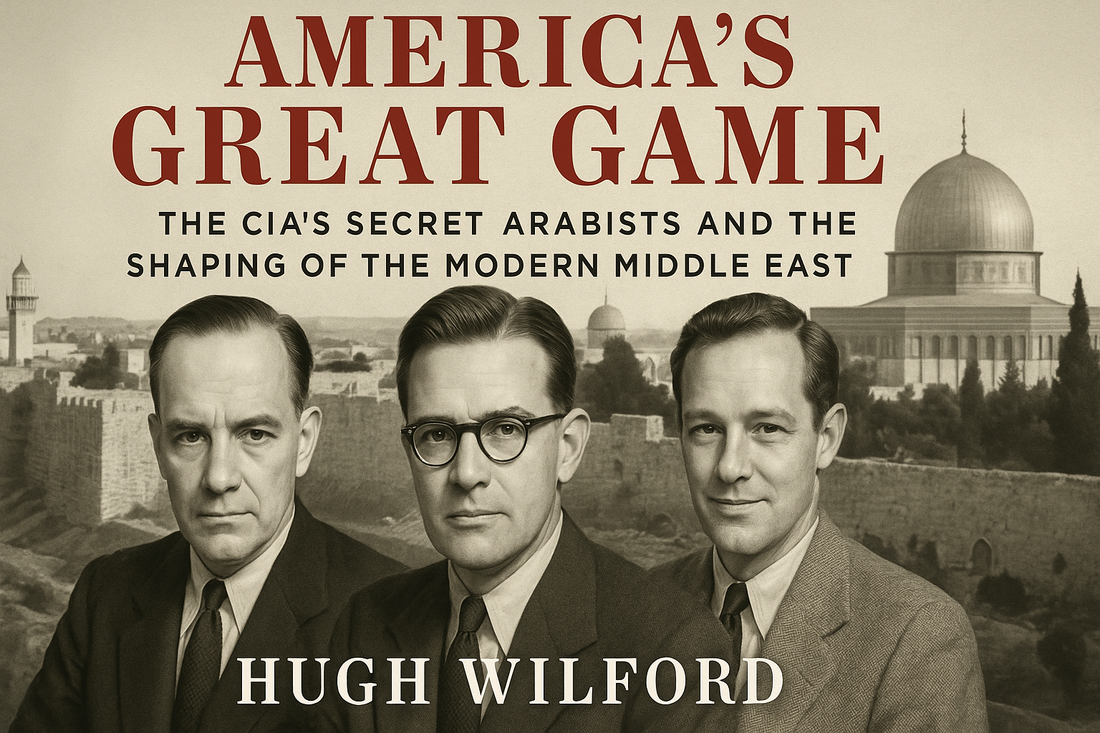

America's Great Game: How the CIA's Arabists Shaped—and Sabotaged—the Modern Middle East

A gripping review of Hugh Wilford's deep dive into the Roosevelt cousins, Cold War coups, and the romantic delusions that defined early U.S. meddling in the Arab world.

One can only marvel at the grand American tradition of fumbling into global catastrophe with the dainty confidence of a debutante armed with a Baedeker guide and a revolver. Hugh Wilford's America's Great Game: The CIA's Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East is an exquisitely exasperating account of such misadventures—a meticulously documented record of men in khakis with Ivy League diplomas and Orientalist delusions attempting to rewire a region they barely understood, and doing so with the solemnity of a Roosevelt safari and the results of a drunken trapeze act.

The curtain rises in the mid-19th century, when the U.S. sent its first cultural missionaries to the Middle East—not with tanks or treaties, but with hymnals and chalkboards. The American University of Beirut was founded in 1866, an educational outpost of Protestant values in a region otherwise dominated by European empires. Until the 1930s, America's involvement was almost admirably aloof: a noble, bookish affection for Arabs, untainted by conquest, much like a fondness for Persian carpets or Renaissance frescoes.

But then came World War II, and with it the CIA's loamy embryonic sack, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). As the British Empire slowly expired with the exhausted gasps of an asthmatic dowager, America stood ready with a twinkle in its eye and a flask in its boot to "fill the vacuum"—a phrase that seems, in Wilford's telling, less like a geopolitical strategy and more like the tragic final words of a university freshman before blowing up the chemistry lab.

Enter our three protagonists, each so perfectly constructed for literary adaptation that it's hard to believe Evelyn Waugh didn't dream them up during a migraine:

- Kermit "Kim" Roosevelt, the cousin of Archie and grandchild of Teddy, who strode into Iran in 1953 and, with all the swagger of a man whose bookshelf included his grandfather's big stick, orchestrated the coup that toppled Mosaddeq. It was an act of geopolitical vandalism that made regime change look as easy as changing your socks, and just about as consequential—until the hangover arrived.

- Archibald "Archie" Roosevelt, the scholarly one, was fluent in Arabic and also skilled in the tragicomic art of American idealism, which involved trying to sell democracy to kings and oilmen without getting sand in the brochures.

- Miles Copeland, the Alabama-born jazz trumpeter turned clandestine puppeteer. The kind of man who could discuss Plato, play bebop, and topple a government all before breakfast, then explain it all as merely "bureaucratic improvisation."

Together, they formed a band of Arabists, romantics who wanted to rid the region of European overlords and replace them with a gentler, more benevolent form of American influence, driven less by oil greed and more by... well, okay, also oil greed, but with an accent that suggested diplomacy rather than conquest. At first, they attempted to support Arab nationalism (Nasser, Ba'athism, and Pan-Arab dreams). But then the Cold War arrived with its icy binary logic, and suddenly it was either Moscow or McLean, Virginia.

As Wilford demonstrates with scholarly elegance and an undertow of despair, the noble intentions curdled quickly. The Arabists' dreams of cultural kinship were swept aside by Eisenhower-era paranoia, Dullesian rigidity, and the rising influence of the pro-Israel lobby. "Crypto-diplomacy"—the shadowy art of whispering to kings and coups in smoky side rooms—flourished. But with every clandestine meeting and CIA-backed gambit, trust was eroded, alliances soured, and the Arab street grew wise to the meddling of men who mistook Lawrence of Arabia for an instruction manual.

Wilford's strength lies not just in his access to archives and declassified files (though these are abundant), but in his gift for biography. The Roosevelts and Copeland are not just men; they are archetypes—tragic, bumbling, sometimes brilliant avatars of a nation that believed it could rewire the world through charm, money, and "tough love." What they accomplished, instead, was laying the foundation for decades of distrust, uprisings, and bloodshed—an unintended legacy as American as apple pie laced with Semtex.

There are set pieces here that should be taught in film school. Kim Roosevelt's cloak-and-dagger antics in Tehran deserve their own Netflix series (working title: The Coup and the Cousin). Archie's tortured allegiance to Arab culture while navigating CIA orders feels like a spy novel written by Edward Said. And Copeland—my word, Copeland—is the kind of rogue intellect that could only have thrived in a bureaucracy where jazz and regime change share equal billing.

In the end, America's Great Game is a deeply researched elegy for a time when American foreign policy was defined by people who knew how to pronounce "Beirut," but who nevertheless plunged the region into a whirlpool of coups, contradictions, and betrayal. It reads less like a conventional history and more like a grainy, overexposed home movie of a wedding that slowly turns into a funeral.

For anyone who has ever asked, "How on earth did we get here?"—Wilford offers a clear, compelling, and crushing answer. We got here, quite simply, by trying to play chess on a map soaked in oil and ancient grievance, using pieces we didn't understand, in a game we thought we'd invented.

And like Miles Copeland said, in the end, there were no winners. Only survivors.

Highly recommended. Though best read with a stiff drink and a globe within arm's reach.